Guilty Conscience at Trinity: Theodore Hall, The Boy Who Stoled Atomic Secrets for Russia

Theodore Hall, graduated from Harvard as a physicist and was hired to work developing the first-ever atomic bomb during the Manhattan Project that helped end World War II. He was but 18 years of age. He soon became a reluctant spy who delivered details about the design of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union.

supporting links

1. In Search Of History - The Boy Who Gave Away The Bomb (History Channel Documentary)

2. Spies Who Spilled Atomic Bomb Secrets [Smithsonian]

3. What Happened To Klaus Fuchs After Spying On Manhattan Project & Oppenheimer [ScreenRant]

4. Spy for No Country: The Story of Ted Hall, the Teenage Atomic Spy [Amazon]

5. How the Soviets stole nuclear secrets and targeted Oppenheimer [Park Record]

6. A Compassionate Spy [Apple TV]

7. Edward N. Hall/brother of Theodore [Wikipedia]

8. Joan Hall/wife [NOVA Online]

9. The Manhattan Project Shows Scientists’ Moral and Ethical Responsibilities [Scientific American]

10. 84 Years Ago, Einstein Wrote an Urgent Letter that Altered History Forever [Inverse]

11. Oppenheimer [That's Life, I Swear Podcast]

Contact That's Life, I Swear

- Tweet us at @RedPhantom

- Listen to audios:

-Apple https://apple.co/3MAFxhb

-Google https://bit.ly/3L2K4Iu

-Spotify https://spoti.fi/3xCzww4

-My Website: https://bit.ly/39CE9MB - Email us at https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/

- If you like to leave a review for an episode, please submit on Apple Podcast or on my website

- Do you have topics of interest you'd like to hear for future podcasts? If so please email us at: https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/

Thank you for following the That's Life I Swear podcast!!

8 min read

Hi everyone, it’s Rick Barron, your host, and welcome to my podcast, That’s Life, I Swear

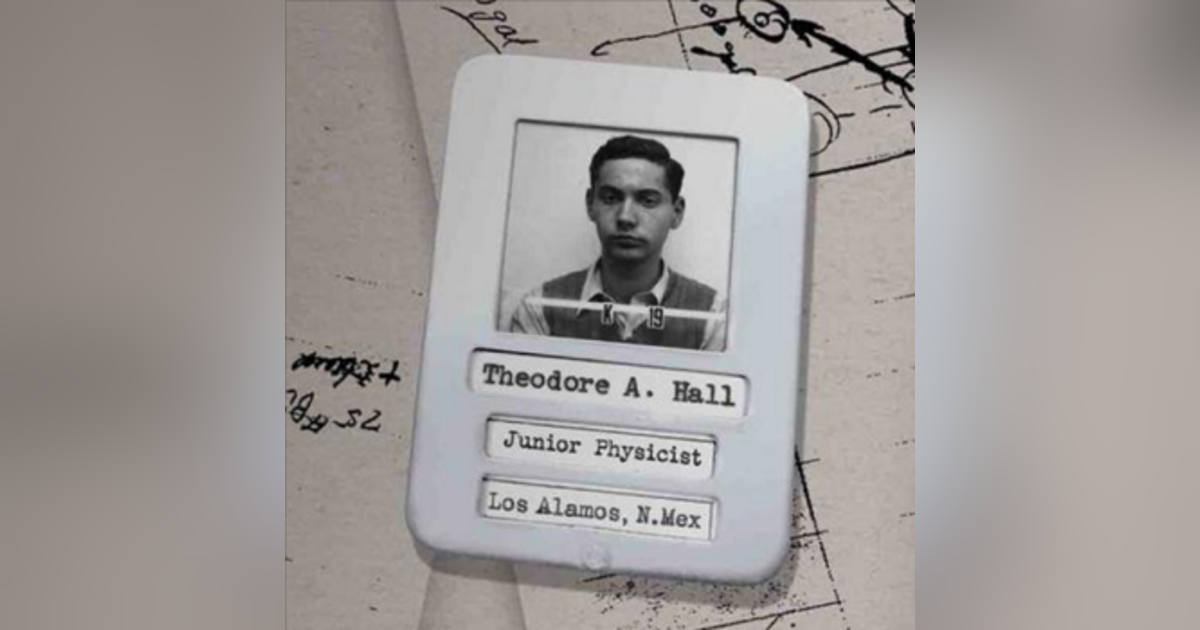

Theodore Hall is a name that doesn’t ring a bell in many history books. It should. He was born in the United States and as a young college physicist, was one of many who worked on developing the first-ever atomic bomb during the Manhattan Project that helped end World War II. I say young because Ted was only 18 when he started work on the atomic bomb. Oh, there is one more thing. He later became a reluctant spy delivering details about the design of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union.

Here’s the rest of this story

A few months ago, I saw the movie Oppenheimer. If you’ve not seen it, please do. It’s a powerful movie and a message for us all.

Towards the end of the movie, heads up, spoiler alert; it was revealed that during the development of the first atomic bomb, a spy had infiltrated into the Manhattan Project. The name of the spy was Klaus Fuchs. He provided information to the Soviet Union about the bomb early on during its development.

Klaus was a brilliant theoretical physicist who left Nazi Germany to Britain and became a British naturalized subject. From the time he started to work on Britain’s wartime atom bomb project, Fuchs was in what he later described as “continuous contact” with Soviet intelligence, providing theoretical calculations that were necessary to construct the atom bomb.

You’re probably saying, ‘Wait, I thought this story was about Theordore Hall.’ It is, so give me a little rope here.

Hearing this information about Klaus, I thought, wait, there was only one spy? Could there have been more? Well, it so happens there was. Enter Theodore Hall. I’ll refer to Theodore Hall for this episode as ‘Ted.’ This is the story of a boy, yes, who was but eighteen when he was recruited to help contribute to the building of the first-ever atomic bomb.

Ted was born in New York City in 1925 and was a whiz kid, a child prodigy. He skipped three grades in elementary school, and his application to Queens College was accepted at14. After receiving a special scholarship, Ted later transferred to Harvard University in 1942, where he excelled in mathematics and physics. He graduated with a physics degree at 18, as one would do. While attending Harvard, Ted became friends with his roommate, Saville Sax. Remember that name.

At Harvard, Hall became involved in the university's wartime defense research efforts.

Prof. John Van Vleck at Harvard recommended that Ted apply for a position regarding a program known as the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, in New Mexico.

Still 18, he applied and was hired as the youngest physicist to work on the Manhattan Project.

When Ted arrived at Los Alamos, he soon discovered the magnitude of what he had walked into. He had some knowledge, but until he went through his orientation and accessed highly sensitive information, that it finally hit him. He was part of a project that would develop the most destructive weapon known to man then, the first-ever atomic bomb.

Ted was part of a team that designed an implosion device to initiate the explosion of the plutonium core of the atomic bomb. That design was tested successfully in the first explosion of an atomic device, code-named Trinity, at New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

After working on determining the critical mass of uranium that would be used for "Little Boy", the first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Ted was assigned to conduct experiments and tests for the complex implosion system of "Fat Man", which would be used on Nagasaki. Remember that Hall was still 18, leading a team of individuals older than him working on both bombs.

In the summer of 1944, Hall realized that Germany was losing the war and couldn’t develop its own atomic bomb. Seeing first-hand the world's first nuclear explosion in July 1945, and it’s immense power, was astonishing and troubling to Ted.

Why does this matter?

Ted was debating about the consequences of an American monopoly on atomic weapons once the war ended. What was especially problematic was the possibility of the emergence of a fascist government in the United States, should it have such a nuclear monopoly and want to keep it that way. He was not alone in his thinking.

Top physicist Joseph Rotblat, resigned from the Manhattan Project, and others like Niels Bohr and Leo Szilard, petitioned first President Roosevelt and later President Truman to put the project on hold and not use the bomb on the people of Japan. Some scientists thought it would be best to inform the Soviets about it, which never happened.

During my research on Ted, it came across my desk that Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, had revealed to a group of top physicists at a dinner that the real target of the United State’s use of the atom bomb was the Soviet Union.

Hearing this information made Ted even more disillusioned with the idea of a nuclear arms race and the potential consequences of atomic weapons. In October 1944, Ted told friends he was returning to his home in New York City for his 19th birthday. It turns out that the claim was false.

The real purpose for Ted’s visit was to stop by at the headquarters of Amtorg, the Soviet Union trading company located on 24th Street in Midtown Manhattan. There, Ted was given the name of a contact, Sergey Kurnakov. It turns out that Sergey was also the same contact for another person, Saville Sax. Remember him? Ted’s Harvard roommate.

Ted and Saville were unaware that Sergey was an NKVD [secret police organization] agent.

Ted quickly passed crucial details about the atomic bomb's development to the Soviet Union. Some of the content provided detailed information about the implosion-type “Fat Man” bomb and several processes for purifying plutonium. Saville was Ted’s courier.

Saville subsequently delivered the same report to the Soviet Consulate, which he visited under the disguise of checking about relatives still in the Soviet Union.

Starting in 1944, Ted and Saville continued passing information to the Soviet Union through their contact in New York. The spying journey ended in 1951 when the FBI arrested Ted, Saville and fellow spy, David Greenglass. Greenglass confessed to spying for the Soviets and implicated Ted.

A side note about David Greenglass: he was a machinist by trade and worked at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico from August 1944 until February 1946.

Perhaps a more critical note about David, is that he provided testimony that helped convict his sister and brother-in-law, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. Both were convicted of espionage and sentenced to execution for their spying activity. As for Greenglass, he ended up serving nine and a half years in prison.

Despite his treasonous actions, would you believe Ted was never prosecuted for his espionage activities with Russia?

Ted later moved to England, where he worked as a biophysicist. He died in Cambridge, England, in 1999 at 74. He was a brilliant physicist and a complex figure who remains controversial in American history.

Now, you’re probably scratching your head and wondering how Ted avoided jail time. With the FBI questioning Ted for many days and hours after his capture in March of 1951, nothing developed that would’ve thrown Ted behind bars. Why?

There are two schools of thought here as to why this may have occurred.

#1 scenario

The U.S. government decided not to pursue legal action against Ted due to concerns that a trial could potentially reveal other damaging secrets related to the Manhattan Project. However, an even a bigger issue needed to be kept under wraps.

The U.S. Army's Signal Intelligence Service, better known as the Venona project (precursor to the National Security Agency (NSA), had a system that decrypted Soviet messages. It was in January of 1950 when the Venona project intercepted a cable identifying Ted and Saville by name as Soviet spies in addition to David Greenglass. It wasn’t until the public release of document’s and many other pages of Soviet wartime spy cables, that in July 1995 nearly all of the espionage regarding the Los Alamos nuclear weapons program was attributed to one man, Klaus Fuchs.

The FBI questioned Ted in March 1951, but he wasn’t charged. The FBI and Justice department claimed this was because their only evidence was the Venona document and that the U.S. didn’t want to let the Soviets know they had broken their elaborate and presumably "unbreakable" code. Alan H. Belmont, the number-three man in the FBI at the time, claims he decided at that information coming out of the Venona project would be inadmissible in court as hearsay evidence, so its value in the case was not worth compromising the program.

#2 scenario

Journalist Dave Lindorff, a writer for The Nation magazine, wrote an article on January 4, 2022 that provided a different twist to why Ted evaded prison time.

Dave obtained on appeal in 2021 through the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI file for Edward Nathaniel Hall. If that last name sounds familiar, it should. Edward was the brother of Ted. The 130-page file included communications between FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to the head of the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, Gen. Joseph F. Carroll, showing that Carroll had effectively blocked Hoover's intended pursuit of Ted and Saville, fearing what Ted's arrest would have, in the political climate of the McCarthy Era. This fear forced the Air Force to furlough so as not to lose their top missile expert, Ted’s brother, USAF Maj. Edward Hall.

Carroll, a former top aide to Hoover before he became the first head of the USAF OSI, ultimately allowed Hoover's agents to question Ed Hall on June 12, 1951 (with an OSI officer monitoring the interview), but restricting the questioning to matters involving Edward himself, not his brother Ted.

Within several weeks of that session, the Air Force, which had conducted and completed its own investigation into Edward's loyalty (having their own investigators question him four times), promoted him to Lt. Colonel, and later Colonel, and elevated him from assistant director to director of its missile development program.

The promotions were a clear slap to FBI Director Hoover. Col. Ed Hall went on to complete the development of the Minuteman missile program, and then, retiring from the Air Force, but at the urging of the Pentagon, went on as a civilian to lead the development of France's own independent IRBM nuclear missile, the Diamant. In 1999 the Air Force honored him, seven years before his death, by adding him to the Air Force Aerospace Hall of Fame.

After reviewing these two scenarios, and my opinion only, it was a combination of both, along with a bit of help from his brother. It was fortunate that Ted had connections in the right places at the right time.

What can we learn from this story? What’s the takeaway?

A year before his death, Theodore gave a more direct confession in an interview for the TV series Cold War on CNN in 1998, saying, and I quote:

“I decided to give atomic secrets to the Russians because it seemed to me that it was important that there should be no monopoly, which could turn one nation into a menace and turn it loose on the world as ... Nazi Germany developed.

There seemed to be only one answer to what one should do. The right thing to do was to act to break the American monopoly.” End quote

Ted was haunted, he explained decades later, by thoughts of how to spare humanity the devastation of nuclear power. Was he a hero or a traitor? You decide. Remember, he was eighteen years old, an adolescent intellect or savant.

Well, there you go, my friends; that's life, I swear

For further information regarding the material covered in this episode, I invite you to visit my website, which you can find on either Apple Podcasts/iTunes or Google Podcasts, for show notes calling out key pieces of content mentioned and the episode transcript.

As always, I thank you for listening and your interest

Be sure to subscribe here or wherever you get your podcast so you don't miss an episode. See you soon.